April was all spent in Chicago working on Ada Palmer’s class simulation of the papal election of 1492. It really does consume the whole month, tweaking character sheets, writing letters, helping orchestrate—there’s barely time to eat, and pretty much all my reading was just reading myself to sleep. I came home to Montreal right at the end of April and did finish a few things on the train. I only read six books all month, and here they are.

P.S. Come to Italy, Nicky Pellegrino (2023)

A beautiful romance novel set in Italy, by Pellegrino, who is my favourite author working in this genre. This is about a woman from New Zealand who lost her husband to dementia before she lost him to death, and who comes through mourning and the pandemic to find a new love in Italy. You can’t tell from looking at this that it’s actually a good and thoughtful book, but it is. Excellent characterisation, funny in parts and moving in others, with very good depictions of friendship.

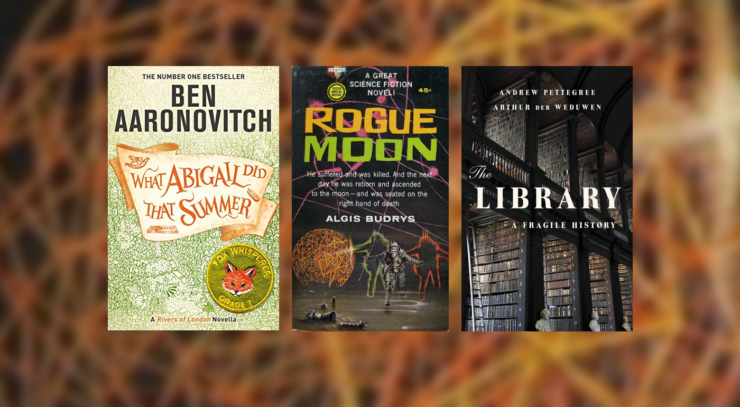

The Library: A Fragile History, Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen (2021)

A history of libraries in Europe and the US (with a glance at the rest of the world) from the very first libraries to the present day. An excellent read, well researched and readable, with a lot of thought put in to why people create libraries and how much easier it is to create them than to maintain them over time. It does not shy away from the horrors of book destruction and censorship, and it also looks with clear eyes at the paternalistic and patronizing attempts to institute public libraries, It’s very interesting to see what has worked over time, and to consider why France is doing so much better than everywhere else right now. A thought-provoking and just generally interesting and enjoyable book.

Rogue Moon, Algis Budrys (1960)

Oh gosh I hated this. You may remember that when I was doing my examination of Hugo nominees I said I thought I’d read this and forgotten it and everyone told me no, I wouldn’t have forgotten it? I think I was right, because although I have no memory of it, I did know I didn’t want to read it, and there was one thing in it that rang a vague bell when I got to it. I generally like Budrys, and I really loved reading his old reviews in Dave Langford’s editions of them a few years ago. But this book… it’s as if someone decided to write a pulp SF story after swallowing but not digesting Freud. It makes no sense on any level.

The characters are all awful people, and they’re badly drawn and given to making interminable speeches about their own and each other’s psychology, which might be all right if they were in any way interesting. The SF plot is “there’s an alien puzzle on the moon and also teleportation beams.” It’s very Hemingway, and not in a good way. I dragged myself through this by my fingernails, and knowing it was short, always hoping there was going to be something worth it there. Huge anti-recommend. I’d be interested in hearing why people pressed me to read it and what I am missing about why this is supposed to be a good book. It’s not often I read something I dislike as much as this.

What Abigail Did That Summer, Ben Aaronovitch (2021)

The novella that goes before the last book in the Rivers of London series that I read. Fast, fun, excellent different voice, loved the footnotes even when I didn’t need them (I know perfectly well what Horrible Histories is) and I hope for more Abigail POV. The only hesitation I have is that this book pushes the series closer to the “do they think I’m stupid?” issue I often have with urban fantasy and its related genres, in that if there’s this much magic etc. around, in what’s supposed to be this world, I would have noticed it. The early volumes dealt with this very well, but as it continues and escalates it becomes more of an issue, and this book made me think about it. Aaronovitch better give me some explanation for why intelligent people living in Britain aren’t aware of all this pretty soon.

The Seashell Anthology of Great Poetry, edited by Christopher Burns (1996)

This really was an excellent anthology, well-thought-through by theme, with a good mix of things I knew and new things, and sometimes juxtaposing poems in provocative and powerful ways. I read this two or three poems at a time over a long time, and am sorry to have come to the end of it. The absolute standout new-to-me thing was Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Art of Losing Isn’t Hard to Master,” but really there was so much here that was so good, it’s hard to single things out. Very well done. I also just looked up Burns to see if he’d edited any other similar anthologies and he seems like an extremely interesting guy.

About Writing: Seven Essays, Four Letters, and Five Interviews, Samuel R. Delany (2006)

I’ve had this book for a long time but only read it now that I picked up an electronic copy. It both is and isn’t a book on how to write; what it mostly is is Delany musing on what literature is. There’s a really fascinating section on canon formation that made me sit up and take notice—he talks about the markers of canon, and the way things are pre-welcomed and considered, and then the fascinating example of Steven Crane. It’s worth reading this whole book for that. I don’t know if I’d recommend this to people wanting to know how to write—there’s lots of writing advice in here, but caught up in a lot of other stuff. A good and valuable book but hard to categorize.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two collections of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections, a short story collection and fifteen novels, including the Hugo- and Nebula-winning Among Others. Her novel Lent was published by Tor in May 2019, and her most recent novel, Or What You Will, was released in July 2020. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal. She plans to live to be 99 and write a book every year.

I just reread Rogue Moon. The bit that really stood for me was the part where one of our heroes admits that while it is clear to him that women have cognitive functionality not related to reproduction, he cannot fathom why.

As much as I enjoy Rivers of London, like many long-running series it does suffer from what I call the “expanding world problem”, where later books introduce elements that it seems like characters ought to have been aware of in earlier books. (Or in other words, at some point you have to wonder how Nightingale could ever have thought he was the last wizard in Britain with all this other magic going on.)

At a certain point Aaronovitch is going to have to go public with magic in his world since its coming back, maybe he doesn’t have to level Leeds the way that Charlie Stross did in his “Laundry” series to make the point, but you get the drift.

I would never – what never ? – say supposed to be a good book about most any book. I might point to the jacket copy on Arslan as suggesting there is something there in a book many find difficult.

I worked in the trucking industry in Chicago while Mr. Budrys was associated with International Harvester

[The Distant Sound of Engines March 1959 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. is a story that could just as well be Hemingway influenced non-genre save for a need to fit the author’s established market]

and in discussing Rogue Moon with him – I liked him personally and enjoyed his writing – we agreed that at least some of the characters could be found around Chicago.

Like say some by David Drake, I suggest that Mr. Budrys could and did draw some characters from life that many at least English speaking readers would never have met or even observed. Taking the fantasy elements in Rogue Moon as McGuffin and even distractions might lead to a different understanding of awful people badly drawn. That is the characters are not the sort of people Campbell bought stories from Heinlein about.

I remember reading Rogue Moon while dutifully working my way through all the Best Novel nominees while in university and just being … thoroughly baffled by its presence on that list.

I’d like to know how Abigail’s friends the foxes decided that they all belonged to a covert organization and adopted the terminology and tradecraft of John Le Carre’s Circus. There was something in one of the books about them being associated with the Faceless Man, but that didn’t make it clear to me.

@1 I’m not surprised a passage like this exists, and yet wow. I still can’t believe someone actually wrote this. What even is this assumption that only women could exist for the continuance of the human race? Did this guy forget that (pre-modern medicine at least) males are involved in the process, too? Why then do men have intelligence? Out of respect for the many thoughtful and considerate men I know, I will refrain from continuing with all the jokes I could make about XY genetics and fitness.

Jo, thanks for doing these. I’ve picked up several books based on these lists.

I think Rogue Moon sticks in people’s minds because the central image – the obsessed scientist and the obsessed explorer, the artefact, the repeated deaths – is a powerful one. But considered as a novel of characters and psychology it’s just bad, and if you’re sensitive to that then naturally you’ll hate it.

Also and belatedly, considering Rogue Moon’s ideas of death and masculinity has me wondering how much better it could have been if James Tiptree had written it

I agree that the psychological stuff in Rogue Moon is dreadful. It still sticks in my mind after fifty years (a) for the alien leftovers – as in the Strugatskis’ Roadside Picnic, and (b) for the questions about personal identity and duplication, which have since become mainstream in philosophical circles.

On Rivers of London: Nightingale was badly traumatized, and so were most other practitioners. Also Cold War secrecy. Magic is only gradually surfacing, but the moment when it must become public knowledge has been signalled several times.

The exposure of magic in the Rivers of London books could turn out to be a damp squib in a couple of ways. An old reason is that people just don’t see the miraculous as such, or discount it as some falsehood (e.g. an advertising gimmick); I’m sure this idea has shown up in multiple genre stories over the decades, although I can’t point to one right now. (This is beyond whatever is left of the English reputation for going about one’s business without acknowledging or fussing about the unusual.) A newer reason is the tabloid effect multiplied by the internet: so many bogus things are made much of that people either believe all of them (but are generally powerless to actually do anything) or believe none of them on the grounds that the source can charitably be called unreliable. I also wonder whether Aaronovitch just hasn’t bothered telling us about the occasional use of the magical equivalent of Men in Black‘s “neuralyzer”.

A treat, as always! I have discovered, and rediscovered, many books thanks to your reading lists, Jo.

An aside: “It’s very Hemingway, and not in a good way” is, sadly, true of most of what Hemingway himself wrote. Except for the short stories, maybe, and not all.

I like Budrys a good deal, and I like Rogue Moon. It’s about obsessive people, like a lot of Budrys’ stories. But I won’t try to convince people to like it.

As for the one character’s absurd ideas about women — I’d like to remind people that just because a character in someone’s books says something doesn’t mean the author believes it. Budrys was portraying a character, and a seriously messed-up character. He wasn’t endorsing the character’s views.

“The Art of Losing” is an all-time favourite. It and “Seascape” wrestle for the top of Bishop’s poems for me:

Heaven is not like flying or swimming,

but has something to do with blackness and a strong glare

I don’t think I’ve actually read the novel Rogue Moon. But I do know the story — back in 1979 when I was in college, my father sent me cassette tapes of a radio dramatization of the novel. I remember at the time thinking that there were an awful lot of words for one interesting idea and nowhere near enough actual plot.

Wikipedia says the novel was adapted into a radio drama by Yuri Rasovsky. (As it happens, I am much more familiar with Yuri Rasovsky’s name from “The Chicago Language Tape,” which was a perennial request on WFMT’s MIdnight Special.)

I haven’t read Rogue Moon, but the reference to “awful people” as characters reminded me of a Haldeman novel where there was a small crew on a space mission. One woman on the crew had two husbands travelling with her, yet she started an affair with another woman’s husband, a younger man called Moon Boy by the rest. He became increasingly unstable, fulfilling his nickname literally, becoming a Luna-tic. She didn’t seem to notice or care that she was the proximate cause of the instability.

The woman’s two husbands observed but remained completely passive and there was no consequence or even criticism of the sexually rapacious woman. Other than the author working out some personal animus, I saw no reason why this soap drama was even part of the story. I disliked the characters so much that a transference occurred to the book and author himself. I chose not to finish and not to read the next volume in the series. Not sure if that series was ever finished. Aside from the awful characters, it became just a bunch of things that happened.

Clark — are “whiny self obsessed people with very period-typical sexism” the kind of Chicago characters people might not have observed you’re talking about? Because that’s my problem with them, and I don’t think it’s a Chicago thing or a working class thing at all — I do think it’s a Hemingway he-man thing. I also don’t think Barker’s disability was done in a way that’s at all either physically or psychologically plausible.

The novella version of Rogue Moon was voted into a Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthology, so a lot of people must have liked it at the time. No idea why.

@7 Some of the other things they’ve said (including in Amongst Our Weapons, the latest book) seem to indicate that their existence dates to WWII or shortly before, and that whoever initially trained them (and possibly created them) was principally concerned about hunting out Nazi spies. That person[s] is definitely not in contact with them anymore, and is probably dead. Given that the Society of the Rose are the group of British practitioners who have access to flesh shaping magic, I would guess one of them was responsible for the business.

@21 – Thanks. I must have missed all this. Should have known that Aaronovitch would have scattered clues to the backstory about.

#19– For a first approximation here I’d say not so much Chicago en mass – though Chicago, as corrupt as it has been, does I suggest bring out the worst in people and put it on display e.g. the Chicago Way – as Teamsters and the trucking industry in general. As a strongly regulated business in a corrupt society trucking brought out the worst in people or at a minimum offered many opportunities for the worst in people to surface. At one time the shuttle migrant inhabited parts of Chicago were the most violent parts of the city presumably as being the most influenced by southern or scots/irish heritage.

I don’t know that I could disentangle Hemingway from where he grew up – Faulkner on the past.

Rogue Moon is a book about a frontier and a frontiersman; some might say the final frontier. Frontiersmen are interesting but not necessarily nice people.

Looking at Chicago:

They tell me you are wicked and I believe them, for I have seen your painted women under the gas lamps luring the farm boys.

And they tell me you are crooked and I answer: yes, it is true I have seen the gunman kill and go free to kill again.

And they tell me you are brutal and my reply is: On the faces of women and children I have seen the marks of wanton hunger.

@22, the foxes are my favorites, but I do hope he doesn’t go _too_ much into detail about where they came from. They work better as they are. Definitely one of the better things to come out of Aaronovitch writing stories about the side characters.

I suppose the idea is that Nightingale and the other traditional powers just didn’t notice that there were lots more magical beings out there than anyone knew, since they were wrapped up in their own problems. That does stretch believability a bit.

@24

Many of the magical beings were largely dormant at least from the 50s onwards, for reasons yet unclear. In October Man and The Hanging Tree we learn that a lot of them were deliberately destroyed, in Europe by the Nazis and elsewhere by various colonial powers. Likewise, WWII didn’t just kill most English human practitioners, it killed almost all the practitioners in Europe. Elsewhere a lot of practitioners went down to colonial armies and diseases, and the Cultural Revolution is specifically cited as doing in pretty much the entirely of the magical community in the PRC. Not specified in text, but I would bet that the Khmer Rouge did a number on Cambodian practitioners as well. By the time Nightingale started to come out of his PTSD funk in the 60s, pretty much everyone he ever knew to be directly involved with the demimonde was dead or even deeper in a funk than him. Mama Thames showed up in the 60s, but didn’t make big waves (metaphorically speaking), and a few other beings awakened then as well. (See A Dedicated Follower of Fashion). Somewhere in there a few practitioners started aging backwards (Nightingale and Sidnarova, but not their surviving cronies. There is no clear reason for this). Around the turn of the 21st century, the pace of magic coming back started accelerating, with fae incursions and at least four new river gods coming into existence over the course of the series, and all that other stuff. Clearly it’s going to start going public again, with Nightingale teaching classes of lawyers and cops to do spells, and Abigail of course.